CRÍTICA, ELOGIO, FETICHIZAÇÃO por Clarissa Diniz

A fotografia ininterruptamente expande-se na arte brasileira não só como linguagem, mas como lógica construtiva de obras que não são necessariamente fotografias, mas pinturas, vídeos, instalações, performances etc. Percebe-se também que muitos dos trabalhos calcados na lógica fotográfica referem-se a uma temporalidade anterior à que hoje vivemos. Colocando de lado os modelos estéticos instaurados com a era digital, tais obras filiam-se à cultura da tecnologia analógica e, muitas vezes, escolhem lidar com uma estética amadora e caseira, incorporando suas habituais “distorções” de luz, foco e composição como virtudes plásticas e conceituais quase sempre desdobradas em discursos metalinguísticos sobre a própria fotografia ou em reflexões sobre a construção e o apagamento das subjetividades. A produção de Marcelo Amorim, por exemplo, relaciona-se a tais procedimentos.

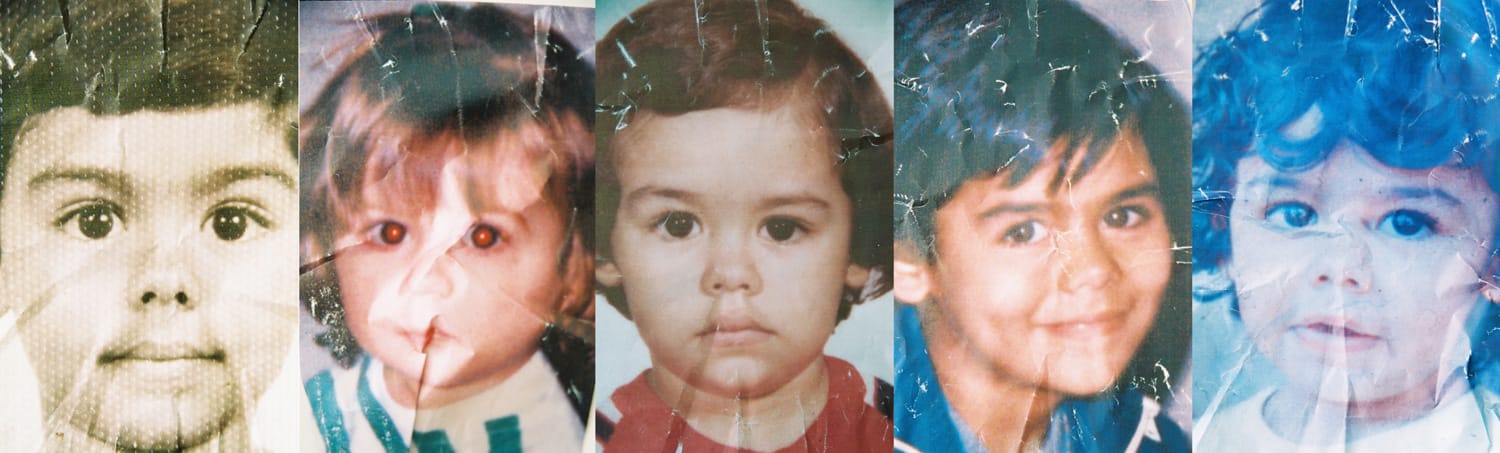

Em seu trabalho, o artista publiciza imagens de acervos fotográficos particulares, reconsiderando seu caráter privativo e suas peculiaridades, ao relocar livremente as identidades que desses acervos fazem parte, descontextualizando-as de seu espaço e tempo de origem. Assim procede Amorim na série Missing, quando recorta rostos infantis de fotografias de festas familiares, retirando-os do relativo anonimato da coletividade para inserilos na lógica do retrato, onde falam mais alto identidade e solidão. Por meio de seu método “sequestrador”, portanto, o artista faz ver a susceptibilidade da fotografia em sua tentativa de suspensão do espaço-tempo, metaforiza a cambialidade das identidades e, por fim, revela certo “autoritarismo poético” na apropriação da intimidade do outro como forma e conteúdo de sua obra.

Por tal “autoritarismo” – que explora a flexibilidade da linguagem fotográfica e apresenta relativo despudor ao lidar com o outro –, a produção de Marcelo Amorim é comumente apontada como transgressora, título que, sob o argumento da criticidade, obscurece um processo de elogio e, talvez, de fetichização do passado que também percebo em seu trabalho. Ao eleger como objeto de sua obra um tempo relativamente distante e, analogamente, trabalhar com uma

tecnologia atualmente em desuso, sem dedicar-se a construir discursos acerca deles – tempo e tecnologia – mas, basicamente, apropriando-se de sua estética mormente por um interesse formal pela linguagem fotográfica, Marcelo, acredito, enfatiza menos um posicionamento crítico em relação ao passado que uma sedução, sem pretensões representacionais, por sua visualidade. Abre-se, assim, espaço para a fetichização.

O movimento de retorno à cultura e estética analógicas da fotografia – conduzido não só por Amorim, como por outros jovens artistas – talvez se encontre, portanto, no imbricamento entre crítica, elogio e fetichização do passado. Tal interesse, contudo, diz muito acerca da atual juventude

brasileira, que, sem desejar esquecer ou combater o passado, problematiza-o com um olhar cúmplice – como o faz Marcelo Amorim ao misturar, aos rostos infantis por ele raptados, também seu semblante de criança, aproximando o outro de si.

*CRITICISM, COMPLIMENT AND FETISHISM*

by Clarissa Diniz

Photography is continuously expanding in the Brazilian art not only as language, but also as the logic that produces works of art that are not necessarily photographs, but paintings, videos, installations, performances etc. Also, various works based on photographic logic relate to past temporality, not the one we live today. Setting aside aesthetic models introduced by the digital era, these works are linked to the analog technology culture and often choose to deal with an amateur, home-made aesthetics by incorporating their usual “distortions” of light, focus and composition as plastic and conceptual virtues often unfolded to form metalinguistic discourses about photography itself or reflections on the construction and destruction of subjectivities. The work by Marcelo Amorim, for instance, relates to such procedures.

In his work, the artist publicizes images from private collections, reconsidering their private nature and particular aspects by freely reallocating the identities that are part of these collections and taking them out of their original space and time. This is how Amorim produced the Missing series: he cuts children’s faces from family celebration photographs, calling them out of relative collective anonymity to insert them in the logic of the portrait, where identity and loneliness speak louder. Using his “sequestering” method, the artist therefore shows the photograph’s susceptibility in his attempt to suspend space/time, creates a metaphor for exchanging identities, and finally reveals some “poetic authoritarianism” by appropriating the intimacy of someone else as the form and content of his work.

Through such “authoritarianism” – which explores the flexibility of photographic language and is somewhat shameless when dealing with the other – the work of Marcelo Amorim is usually considered transgressive, a title that under the argument of criticism clouds the process of complimenting and, maybe, fetishizing the past that I also notice in his work. By choosing a relatively distant past as the object of his work and analogously using technology that is no longer used, not attempting to build statements about them – time and technology – but basically appropriating its aesthetics purely out of formal interest in the photographic language, I believe that Marcelo focuses less on a critical stand about the past and more on seduction with no representation intentions, because of its visual aspect. So, he creates room for fetishism.

Perhaps, the movement of returning to the analog culture and aesthetics of photography – conducted not only by Amorim, but also other young artists – may be found in overlapping criticism, compliment and fetishizing of the past. Such interest, however, says a lot about the current Brazilian youth, who, with no intention to forget or fight the past, see it as a problem with an accomplice point of view – which Marcelo Amorim actually does by mingling the children’s faces kidnapped by him with his child’s countenance, thus bringing the other close to himself.

Text published in 2008 in the folder of the solo exhibition Missing, held at Centro Cultural São Paulo, São Paulo.